Why YouTube Can't Teach You Everything (And Why That's Actually Good)

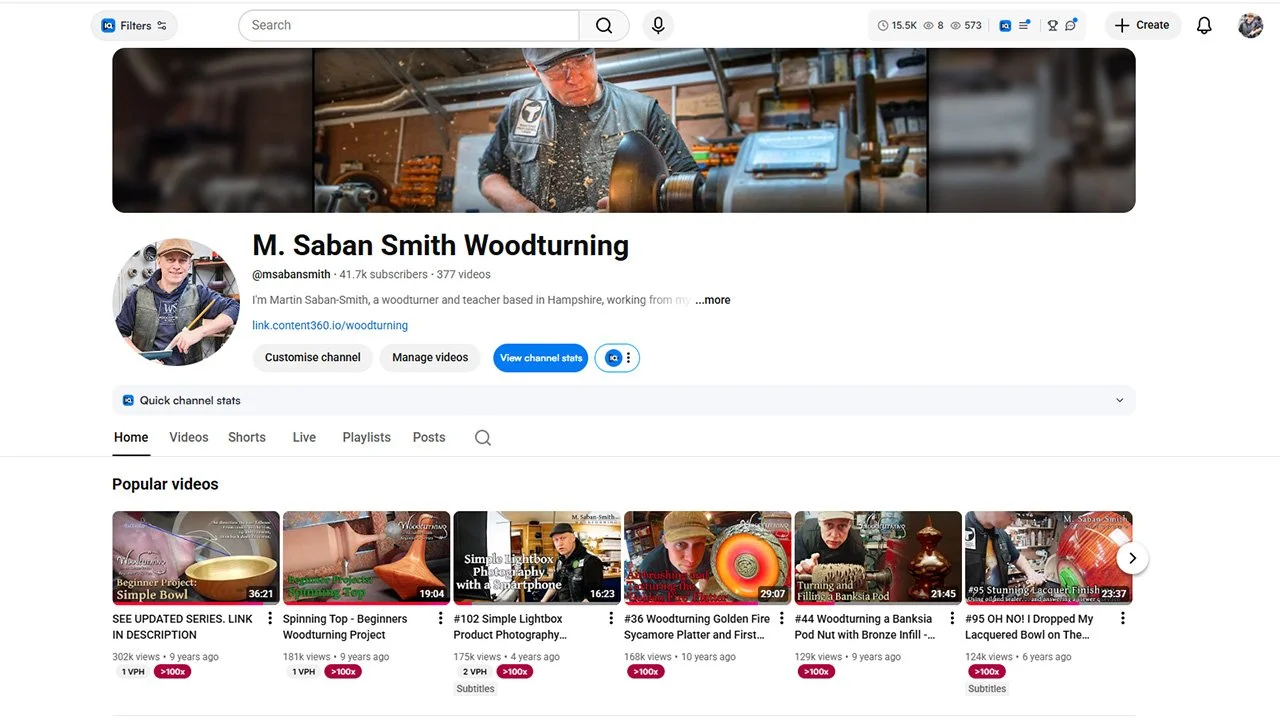

I've made nearly 300 YouTube videos about woodturning. People watch them, learn from them, sometimes even tell me they've changed how they work. I'm grateful for that. The platform has been extraordinary for spreading craft knowledge.

But I need to tell you something that might seem contradictory coming from someone who's invested thousands of hours in online content: YouTube is a brilliant starting point, but it's a terrible finishing school.

Here's why that matters, and why it's not actually a problem.

The Illusion of Completeness

When you watch a well-made turning video, you see smooth cuts, clean finishes, and confident movements. The tool behaves. The wood cooperates. Everything makes sense.

What you don't see is the decade of muscle memory that makes those movements look effortless: the countless minor adjustments happening below the level of conscious thought. The reading of grain, vibration, and sound that experienced turners do automatically.

You're watching the performance, not learning the rehearsal.

This creates a gap between conceptual understanding of what should happen and the ability to make it happen with one's hands. You watch someone present a gouge at the "correct" angle, and it looks simple. Then you try it, and nothing works quite right.

The problem isn't you. The problem is that psychomotor skills require physical movement and coordination, which can't be fully transmitted through observation alone.

What Screens Can't Carry

In "A Maker's Mindset," (coming soon), I write about attention as the foundation of craft. However, there are different qualities of attention, and some require physical presence.

Feel. The resistance of wood under the bevel. The difference between cutting and scraping. The required pressure varies with each species, grain orientation, and tool. You can describe this in words, but words don't teach your hands.

Real-time correction. When you're learning online, you make a mistake, realise it (maybe), and try to correct it. But by then, you've often reinforced the error. An instructor beside you identifies the problem as it's forming: your stance, the grip, the tool angle, before it becomes a pattern.

Adaptation. Videos teach general principles. But the wood you're turning right now has specific characteristics that demand specific responses. An experienced teacher reads your piece and guides you through the unexpected. The video keeps playing regardless.

Safety intuition. Yes, you can learn safety rules online. But safety in making is also instinctive by recognising when something feels wrong before you can articulate why. That develops through proximity to someone whose instincts are already honed.

The Research Backs This Up

Studies on psychomotor skill acquisition* consistently show that the optimal instructor-to-student ratio for hands-on learning ranges from 1:2 to 1:6, depending on task complexity. Below that ratio, learning efficiency drops significantly.

Why? Immediate feedback is the most important variable for motor skill development. The gap between action and correction needs to be as small as possible. Do something wrong, get corrected immediately, and try again. This loop is tight and fast, and is how physical skills are built.

Online learning can't provide that loop. The gap between your action and any feedback (if you even recognise you need feedback) is too large. You've moved on, tried something else, developed compensating habits, before you even know you were off track.

What I've Learned Teaching Both Ways

I teach both online and in person. The difference is immense.

Online, I can share knowledge. I can explain principles, demonstrate techniques, and show what good work looks like. Students build conceptual understanding, learn vocabulary, and develop their eyes.

In person, I can shape practice. I can see what someone's doing wrong before they're aware of it. I can intervene precisely when it matters. I can offer encouragement when doubt appears on their shoulders before it reaches their conscious mind.

Both matter. But they're not interchangeable.

The students who progress fastest are those who use both online learning for breadth and inspiration and in-person instruction for depth and correction.

The Uncomfortable Economics

Here's the part that makes me slightly uncomfortable to write: in-person instruction costs more. Significantly more. A YouTube video is free. A class requires travel, time, and tuition.

I understand that barrier. I've been broke enough times to know that "just book a class" isn't always viable advice.

But here's what I've also learned: the cost of developing bad habits through unsupervised practice is higher than it appears. Six months of solo learning based on videos can embed patterns that take longer to unlearn than if you'd started with proper instruction.

Time is the currency we often forget to count. The frustrated hours spent wondering why the technique you watched looks nothing like what you're producing. The pieces were abandoned. The growing sense that you may not be cut out for this.

At a talk I gave in London back in November 2025, I mentioned that if I could go back and learn from the beginning again, I would do so with a teacher instead of waiting for three years.

Good instruction accelerates past all of that.

**So What's the Answer?

Use YouTube. Absolutely use it. Build your knowledge base. Study different approaches. Get inspired. Join the conversation. The online woodturning community is generous and valuable.

But recognise its limits. And when you're ready, or perhaps slightly before you think you're ready, put yourself in a room with someone who can see what you're doing and help you do it better.

The combination is where real development lives.

At The Woodturning School, we keep classes small (maximum five students) specifically because psychomotor skill development requires attention. Les Thorne and I are both Professional Turners. We're not special. But we've made enough mistakes to recognise them forming in others, and we've taught enough students to know when to intervene and when to let struggle do its work.

That's what in-person instruction provides: presence, attention, and the kind of feedback that closes the gap between watching and doing.

*"Research on psychomotor skill acquisition consistently demonstrates optimal instructor-to-student ratios for hands-on learning. A randomised controlled study in Medical Education found the optimal ratio to be 1:4, with both higher and lower ratios producing significantly less learning (Dubrowski & MacRae, 2006). Systematic reviews of health care skills training recommend ratios between 1:2 and 1:8 depending on complexity, with 1:2 being identified as the most efficient for quality learning in complex motor skills (Snider et al., 2012)."